Long a Caillebotte fan, I consider him the lost Impressionist. He was a temperamental character who was more influential in the development of both modern art and racing yacht designs than many people - even art or yachting aficionados - realize. Because Caillebotte was the son of a wealthy Bourgeois in mid 19th Century France, he did not work for a living, yet he lived in luxury, unlike most of the more famous Impressionists. He painted because he wanted to: a gentleman’s pursuit. He also collected art and upon his death left the nation of France a legacy which a century later became the nucleus of Paris’s Musee D’Orsay.

As my hero Kirk Varnedoe, legendary art historian and Chief Curator of Painting and Sculpture at The Museum of Modern Art in New York wrote in his essay Odd Man In: A BRIEF HISTORIO-GRAPHY OF CAILLEBOTTE'S CHANGING ROLES IN THE HISTORY OF ART:

Despite the rhetoric of its early advocates, the success of Impressionism did not arrive by destiny. It required, beyond the achievements on the canvases and the serendipity of circumstance, hard work on the part of several individuals among whom Gustave Caillebotte was one of the most dedicated. He haggled and negotiated to keep the group together through periods of fractious disagreement; and when he had to, he rented the exhibition space, paid for the advertising, bought frames, and hung the pictures. In what would now be called the management and marketing aspects of Impressionism, he was an indispensable asset.

One of the founders and funders of the Impressionist movement, Caillebotte’s role in the development of Modernism was pivotal, perhaps less for his painting than his tireless advocacy and collecting. He paid Monet’s and Renoir’s studio rents. He bought paintings by the scores, for which he would pay the artist inflated prices. He would pay more than the paintings were worth – more than the artists were asking for them - so that they could go to the next patron and say “my last painting fetched THIS much…,” and increase the price of their work. He was in on the selection, and arrangement, and all other details of the Impressionists’ Salons, even exhibiting his own work to some critical success.

The collection he amassed, much of which he left to France, stayed either in private hands or museum vaults until a couple of Impressionist exhibitions and the opening of the Musee d’Orsay in the 1970’s reintroduced his collection and his work to the world. His Renoirs, Degas, and Monets form the basis of the Orsay, perhaps the most impressive collection of Impressionist art in the world, and to him we owe thanks for his vision of a “new art,” which over a hundred years in the forming, forgot him along the way.

Gustave Caillebotte made other contributions as well. Many scholars consider his painting style too academic or realistic for him to be an Impressionist, but his subject matter and approach to perspective were radically new, and very much in the Impressionist spirit. The seemingly haphazard arrangement of colors and white in the Fruit Displayed on the Stand at the MFA, the severely exaggerated angles and clearly impressionistic rendering of the puddles and rain in Rainy Day – Paris, the overbearing foreshortening of the dining table in Luncheon mark Caillebotte’s work as radical for its time.

His paintings of butcher shop windows with calves' tongues and dead birds were shocking. His Floor Scrapers were to working class men what Degas’ Laundresses and Dancers were to working class women: treated by the Impressionists, these are a new take on the peasant/servant scenes so popular generations before in Dutch and Flemish art, and so romanticized by earlier generations of French artists. These are men in the act of hard labor. They are not rollicking peasants or scrubbed-clean shepherds. They are shirtless, sweaty and filthy. Though recognized for his skill, his choice of subject was deemed unsuitable by the reviewers of the Salon where the painting was first shown.

His later boat scenes and garden views may fade into the Impressionist morass, but his male nudes set him apart as the first artist to have painted nude male figures which were not heroic, historical or biblical (here: Man at his Bath from London’s National Gallery), or as I like to call this series Bob at the Bath. Now, partly due to his own perseverance in putting together the first major collection of Impressionist art and insuring that it stay together until public taste demanded it be taken seriously and placed in its own museum, Caillebotte has come full circle; his collection is appreciated by the world and his work is becoming known.

His later boat scenes and garden views may fade into the Impressionist morass, but his male nudes set him apart as the first artist to have painted nude male figures which were not heroic, historical or biblical (here: Man at his Bath from London’s National Gallery), or as I like to call this series Bob at the Bath. Now, partly due to his own perseverance in putting together the first major collection of Impressionist art and insuring that it stay together until public taste demanded it be taken seriously and placed in its own museum, Caillebotte has come full circle; his collection is appreciated by the world and his work is becoming known.Aside from painting, Caillebotte also had passions for gardening and for yacht racing. His gardens and yachts appear in many of his later paintings. His boat designs radically changed the profile of the racing yacht and resulted in the sleek racing yachts of today, vastly more streamlined and faster than before he became a record-setting captain in boats of his own design. But in his early years, painting was his primary passion.

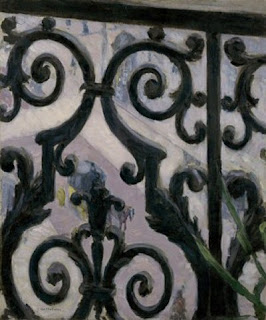

View from a Balcony at the Van Gogh Museum is classic Caillebotte. It has a lot of what I would look for in a Caillebotte. It’s a very high angle view, a typical vantage for this artist who consistently chose “different” angles than other artists. We are looking through the railing of his apartment on the Boulevard Hausmann in Paris, brand new, imposing and expensive. Caillebotte painted several views of this balcony, some looking down and some with men standing on it admiring the view, and begging questions of the viewer.

Caillebotte was obsessed with what we would now call modernity and this balcony was the height of modern in its day, overlooking the newly rebuilt and completely “modernized” Paris. I posit that Caillebotte was in a way trapped on this balcony. Though he had a mistress, or female companion, for several years, he never married: an unusual feat for a wealthy man in Paris of the 1880’s. He painted several canvases of men leaning on this balcony, the male Bathers, the series of Floor Scrapers, the male House Painters and mostly men in his street and boating scenes, leading some to speculate that in today’s parlance, Caillebotte might have been “gay”

Though he had a mistress, or female companion, for several years, he never married: an unusual feat for a wealthy man in Paris of the 1880’s. He painted several canvases of men leaning on this balcony, the male Bathers, the series of Floor Scrapers, the male House Painters and mostly men in his street and boating scenes, leading some to speculate that in today’s parlance, Caillebotte might have been “gay”  or “bisexual.” Though those labels did not exist as such in the 1880s, and the social identities of gay and bisexual persons did not exist as they do today, certainly homosexual behavior and attractions did, and perhaps he was. His paintings of men are often as tender as and his nude men as erotic as some of Renoir’s women.

or “bisexual.” Though those labels did not exist as such in the 1880s, and the social identities of gay and bisexual persons did not exist as they do today, certainly homosexual behavior and attractions did, and perhaps he was. His paintings of men are often as tender as and his nude men as erotic as some of Renoir’s women.

In View from a Balcony, there is a carriage in the center of the canvas heading down the diagonal stripe of the Boulevard. There’s a round poster kiosk in the background and a lone pedestrian at the very bottom of the scene. But what dominates the composition and what makes it classically Caillebotte, is the iron railing.

Here he is giving us with this railing what he gave us with the fruit stand, and the butcher window: a shocking new perspective on a scene we might see every day, and which popular taste of the day would not consider worthy of being recorded in oil on canvas. He has filled the canvas with the iron railing and the street scene below is in a hazy, misty, mauvy background, so that there is an almost solid barrier between the viewer and the city below. The street scene is a little blurry and in a very pale palette, but the railing is black, heavy and wrought iron. It dominates the canvas, creating a daring take on the classic landscape or street scene.

With the number of paintings of men which Caillebotte painted on this balcony, one may wonder if there is some psychological statement here of entrapment. If he were gay, as some of his subject matter might suggest, was he acknowledging that he lived behind a barrier, perhaps the barrier of public acceptance of his supposed attractions or relationships? Whether or not he was gay, he has created a claustrophobic scene out of a landscape, a format which is usually so open. He has created a cage out of a window. One must wonder.

Admittedly, Caillebotte’s View from a Balcony is not the best painting in the world, nor is it the most complex, largest or most valuable. It is however, exactly what the Impressionsists hoped to create: art with a new perspective. Here that new perspective is trapped, tight and claustrophobic, perhaps a parallel for life in Paris at the time. In a painting with very few scenic elements, Gustave Caillebotte has managed to create a work which both pushed the boundaries of what was acceptable in art in his day, and begs questions of its viewer in ours. As Kirk Varnedoe concludes:

And indeed, Mr. Varnedoe, you are not. I would add that Caillebotte’s best canvases are “more rewarding than” any Pissarros, Renoirs or Monets “of the same period.” His perspective is just that different and truly modern.

Gustave Caillebotte - The complete works by Gustave Caillebotte User comments, slideshow, eCards, biography, more than 200 images of paintings and more!

Sometimes I wonder if we apply our modern eye and our own latent feelings too much when analyzing paintings of the past. To me, the nude bather holds no sexual appeal and seems to be rather tongue in cheek, a play on Renoir and Degas.

ReplyDelete